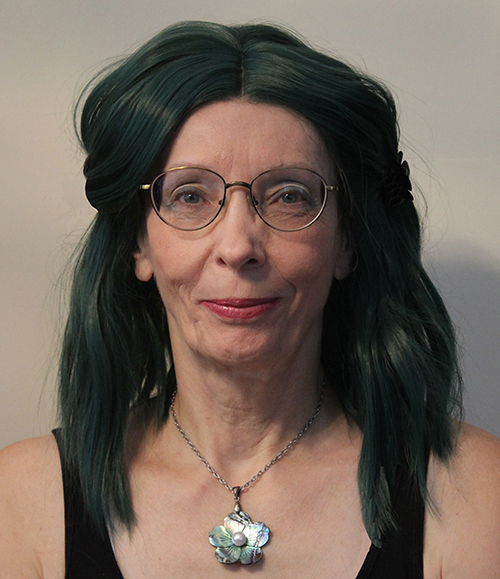

I like to describe myself as a writer and decipherer of fairy tales, a person who is attracted and captivated by – and also writes about – this world’s many wonders. What amazes me most about tales and myths is the cryptic language they employ, a mode of expression that manifests all that humankind has experienced since it first appeared on earth. For years I sought to answer the question: “Why are fairy tales, seen as a children’s genre, and myths, which reflect our past in so mysterious a way, so important that they still earn a place in our lives today?”

I’ve written a variety of studies, essays, poems, and books on the subject and have led – and still lead – “folk tale decryption” groups, all in the hope of seeing a return of this forgotten archaic language to everyday life, of effecting an internal reunion of the dream and reality that – being of the same essence – both shape our reality.

My drive to study mythology and to seek the hidden – even forbidden – knowledge it holds derives from a desire to reclaim the messages bequeathed to us, through myths and tales, by our ancestors. For an overview of my published writings, information on my various books, and a selection of my poetry, see my Web site at www.mesecsoport.hu.

When I was a child, I wanted to be an archaeologist, a desire to which my environment took a rather dim view. To those around me, archaeology seemed too abstract, too intangible an occupation to consider, one that was neither “proper” for me, nor potentially lucrative enough. Their ideas of success left no room for such things, and in the end, it was this general expectation that won out: I did not become an archaeologist.

For me, the concept of archaeology belonged to a private fantasy world I populated with all manner of imagined people, figures, settings, furniture, and what-if events. In retrospect, it might be just as well that I did not study archaeology, that is, learn the “science” and in doing so, give myself over to the rules that bring acceptance and success in the academic world. Instead, I remained free to play with my ideas, without being told what to think, believe, or communicate about them. The result of this freedom was that my curiosity toward various mysterious (i.e. inexplicable) tokens, objects, and signs flourished, leading me in directions influenced by none but myself.

It was, in fact, in the spirit of this curiosity that I visited the pyramids of Mexico, Peru, and Cambodia. I wanted to feel the energy that radiated from such places; touch their rough stones; enter their structures and feel the weight of the rock mass suspended over my head; wonder at the work of long-gone master builders; listen to the echoes off hard stone walls; look down from peaks with no railings at the tempting depths below their steep inclines; and, of course, speculate as to how, for what reason, and to what purpose they were created.

The same love of archaeology awoke in me when I first read of Brynhildr, the slumbering Valkyrie, whose story I had known something of before, if in the superficial manner of a general education. When I began looking into the reason for her sleep, however, and felt that old passion for archaeology begin to stir, I felt I had to get to the bottom of what exactly happened to her. I began to read about her and learned that her story was found in one of the sagas. It was in this way that I got my first taste of Old Norse literature.

In fact, the Old Icelandic manuscripts were written by many hands through periods that spanned centuries. Most of their sources remain unknown, and as their authors differed from one another in style as much as any two writers today, each story bears the mark of the scribe who put it to paper. This individuality extended to everything from the beauty and readability of the script itself, to the abbreviations used, to the influence of the writer’s Latin education or Christian worldview.

And yes, I witnessed these phenomena first-hand, as the Icelandic institutes and libraries have made scanned copies of these original manuscripts available on-line for anyone to use. Driven by my own need for understanding, I began to learn the language, study the texts, and compare them to the transcriptions found in books. It was a remarkable experience when something that had previously seemed a random sequence of letters first resolved itself into an identifiable Old Norse word! In truth, this was a form of archaeology all its own – archaeology with a splash of linguistics and a pinch of cryptology. What could possibly be more exciting? The unpunctuated lines of manuscript text slowly began to take on meaning, and I began to see where one word or sentence ended and another began, which abbreviation meant what, and where the word I just happened to be looking for appeared on the page.

The book my co-author and I have written and to which this Web site pertains is a product of this internal passion, and I hope that its readers will find in our communication of the Icelandic texts all the beauty, intrigue, and depth that, in my research and writings, have given me such joy.